Posted on July 29, 2022 by Ed Tolman

I believe that neither I nor too many other Torah commentators could have written a more cogent and concise drash on this week’s Torah portions, Matot and Masey, than is expressed in the Hebrew words above. These parashiot, the penultimate and ultimate of the Book of Numbers, are combined this year so as to assure the completion of the Torah reading cycle within the year. And while, as is usual, there is much fodder for discussion in these two portions of Torah, I’ve homed in on two events which, I believe, relate in their teachings to the world in which we today live. They are events, which engender the often difficult personal and sometimes public problem of balancing self-interest, self-need, and even self-want against the best interests, needs or wants of others, of our families, our community and of the world at large in which live. As the late Rabbi Fields adds, the events to which I will refer, raise the questions of loyalty to self as opposed to loyalty to community or family and of putting aside self-interest for the good of one’s nation or one’s people.

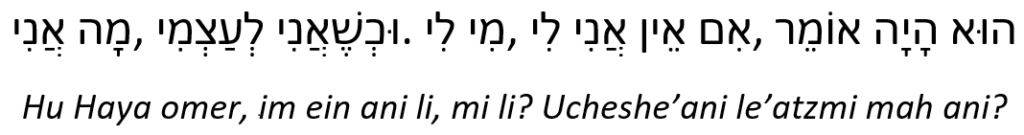

The opening words, with which I know you to be very familiar, are from Pirkei Avot (the Sayings of Our Fathers) Chapter 1, Mishnah 14. They read in English, “He used to say (who is the ‘he’; he is Rav Hillel), ‘If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And, if I am for myself alone, then what am I?’”. The passage, or course, famously ends with the question (not in the preceding Hebrew), “And, if not now, when?”

In our Torah portions, the Israelites find themselves on the west bank of the Jordan river, about to cross into Canaan, the Promised Land, knowing that a great battle is ahead of them. Men from the tribes of Reuben and Gad, reasoning that their tribes are cattle herders and the land already conquered is cattle land, request of Moses that they should remain in place and not move across the Jordan. Moses reacts angrily asking the question of why those two tribes should be allowed to hang back while the others cross the Jordon and do battle. He further accuses them of acting like their forbearers, referring to the twelve scouts who had been sent to survey the land.

Though all had seen the same, a land of milk and honey, it seemed to all but two to be inhabited by fearful giants and to be unconquerable. The scouts had turned the minds of the Israelites against entering the land God had promised them. Jay Lavroff spoke eloquently of this when he presented his drash on Parasha Shelach Le’cha, the opening portion of the Book of Numbers. Hearing this, the Reubenites and Gadites relent by asking for only time to build enclosures for their sheep and towns for their children and saying that, thereafter, they would act as shock troops in the vanguard of the attack into Canaan. Furthermore, they would remain in the Promised Land until all the rest of the tribes were in possession of the lands that were promised and portioned out to them. Commentators accuse the tribes of Gad and Reuben of greed and of putting their own self-interest ahead of the welfare of the greater community. That by putting in their request for time the building of sheepfolds ahead of the building to town for the children, they were placing personal material gains ahead of humanitarian considerations. And yet, in the end, we see that the tribes of Gad and Reuben did relent for the greater good of the community.

Later, in Parasha Masey, we return to the story of the five daughters of Zelophedad of the tribe of Manasseh, son of Joseph. As we remember from last week’s Torah portion, Pinchas, the women had petitioned that they should inherit their father’s land, the father being a brave warrior but not part of the Korach rebellion. This was at a time when land was only to be inherited by males of the family. Moses presented their argument to God and God, in determining it to be just, acceded to their plea. In Parasha Masey, representatives of the tribe of Manasseh, the tribe of those five women, raise the concern that if the daughters were to marry outside of their tribe, the land they inherited would eventually go to the other tribe, thus diminishing the ancestral portion. Agreeing that this also was a just argument, God decrees that while the women could marry whomever they pleased, they would have to marry within their ancestral tribe. And the daughters did as they were commanded. The women acted in deference to the greater good.

Referring to Parasha Pinchas, Midrash holds that when Moses learns that his successor would be Joshua, he argues with God that his own son Gershom should be his successor. But God explains that Joshua has demonstrated more than anyone else his full devotion to the community. And Moses agrees. Moses, in his infinite wisdom, chooses the greater good over self-interest. As Rabbi Gluck taught last week, Moses’s actions were motivated by the humility of a great leader concerned above all else with the needs of the people. He put aside ego and personal needs.

As we look at our world today, we can ask ourselves how well we balance self-interest with the common or greater good. How well we share our own assets of time, energy and, yes, finances with our families and with our communities. How do our business leaders reconcile the needs of stockholders with those of customers and, in some cases, of the environment? How do our elected officials rank party versus country or the desire for re-election versus support of a common cause sometimes antithetical to one’s own political philosophy? How do we, each of us, respond to the teaching of Rav Hillel.

With these words and the few that follow, I honor all those who to go towards the fray, who put themselves in harm’s way, who serve on behalf of us all; the men and women of our military services, all first responders (police, firefighters, emergency medical personnel), frontline doctors and nurses and their support staffs, our own caregivers, those who accept the responsibilities of leadership sometimes at great personal sacrifice and the many more who act for the greater good above and often at the expense of any concern for self.

I conclude this commentary on the final two parshiot the book of Numbers with words traditionally spoken when we conclude a book of Torah, “Chazak, Chazak, V’nitchazeik;” Be Strong. Be Strong. Let us bring strength to one another.

Ed Tolman

Guest Darshan